Analyst: Laura Hopkins

(Note: this article was damaged during an interruption of service to our site. Because it is very popular, I have been working to reconstruct it. -- EGR)

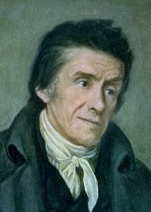

The Educational Theory of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi

©2013 NewFoundations

|

Analyst: Laura Hopkins |

|

RETURN

edited 11/19/18

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi was born in Zurich in the year 1746; he lived to the age of 81. Pestalozzi was very interested in philosopher/theorist Jacques Rousseau. It was following Rousseau's ideas that Pestalozzi would explore how he could develop and use them for himself.[1] Pestalozzi was a very determined individual who even when he hit bumps in the road, he moved on and would eventually succeed. Johann would struggle at the start of his becoming a teacher, but in the end he would become an influence on the elementary schools in the United States today.[2]

Pestalozzi attended the University of Zurich for his schooling and from then on would run all types of experiments in education by opening schools for all types of individuals, usually the poor. However, most of these schools did not last very long and usually fell apart because of a lack of money.[3] Also in his lifetime, He wrote books based on the theories that he had about education. "Children should learn through activity and through things (hands-on tools). They should be free to pursue their own interests and draw their own conclusions." When Pestalozzi argued that there was a need for balance, that the three elements of head, heart and hands is what is most important to children receiving a great education.

Pursuing this balance of hands, heart and head Pestalozzi did away with the punishment upon kids known as flogging, because as a part of the heart there should be love, without love, head and hand cannot develop.[4] Pestalozzi wanted to move schooling away from education as an old way of using old teaching methods. It is because of this that Pestalozzi became concerned with everything dealing with school, children, and the idea that children should be finding out things (answers) for themselves. Johann was about putting that which is right and good before that which is correct because he cared more about people and their well-being than anything else.[5]

I. Theory of Value: What knowledge and skills are worthwhile learning? What are the goals of education?

Since the goal of education is to educate the whole child by balancing between hands, heart, and head,[6] Pestalozzi argued that the knowledge and skills that are most important to learn are: arithmetic, geography, science, music, drawing, language, and physical education.[7] He saw arithmetic as the most important because it is based on sensory experience. According to Pestalozzi, part of the arithmetic that children should be taught is how to understand numbers and how two and two make four. To do this he encouraged mothers to let their children count objects found in the home.[8] When it came to the studies of geography and science, Pestalozzi made it so that the students would learn about both form an entirely hands-on approach by taking walking tours of their neighborhoods while looking at the environment around them, they would also see the types of land forms and weather patterns of their specific area.[9]

Pestalozzi viewed music as an important part of the elementary curriculum; he believed that music would be the key to a moral education because in his words "music speaks to the heart".[10] As you can see Pestalozzi viewed all of the major subjects as important to learn in the elementary education curriculum. Drawing, language, and physical education were also very important because drawing expressed the individual's talent. Language was also important in order for students to express their feelings and beliefs.

Lastly, Pestalozzi saw physical education as important because in his time physical education was neglected and children were not allowed to move in the classroom. As a result of this Pestalozzi believed that for full development, not only did mental and moral qualities count, but physical capacity was also extremely important in making children flexible and strong.[11]II. Theory of Knowledge: What is knowledge? How is it different from a belief? What is a mistake? A lie?

Knowledge is the information that someone receives as a result of learning and searching for answers. Pestalozzi believed that if the teacher is not to impose ideas on the child, then he must rely on the child and his immediate environment for the knowledge he wishes to communicate.[12] If the teacher is not going to pour the knowledge into the children's brain, and then it will be up to the child to find the knowledge on their own. Pestalozzi also sees observation as the absolute basis of all knowledge; therefore without the child being observant to their surroundings, they will not be able to get all of the answers needed to succeed.Knowledge is different from belief in this aspect because belief is a principle or something someone believes in, it doesn't have to be true or false. Knowledge however is strictly fact and is something that has been proven over time and taught for many of years. Pestalozzi was not happy with the way the content of education was being presented as fact rather than as experience.[13] Looking at it this way it is clear that Pestalozzi would rather have had students learn from their own beliefs rather than the knowledge of teachers just forcing ideas on the children.

Mistakes are something that people make when they assume something that may not be true. Pestalozzi mentioned how the most important mistake of education today is that too much is expected of the child and too many of the topics only appear to be something but are nothing.[14] A lie, in contrast to a mistake is when someone knows that what they are saying is not the truth but they chose to say it anyways. Pestalozzi does not believe it lies in his theory on education only the one big mistake that some make about education.

III. Theory of Human Nature: What is a human being? How does it differ from other species?

Human beings are able to use powers that set us apart from other species. As Pestalozzi explains, these include intellectual, practical, and moral powers.[15] Human beings are able to experience things differently than other species in the world, intellectual and smart. However, Pestalozzi believes that in order for us as humans to be intellectual we must become aware of our five senses, seeing, tasting, feeling, smelling, and hearing.[16] Without these important five senses there is no way we can be intellectual because we would not be aware of what is happening around us in the outside world.

Perhaps the most important part of being human is the moral powers of the heart which make us feel all types of emotions. Pestalozzi ranked this power as number one on his list because it is feelings of concern, compassion, gratitude, grief, joy, pride, and others that truly make us different then animals, it is our conscience that guides us and according to human nature from Pestalozzi's view, man follows his conscience.[17]

In Pestalozzi's own words "Man's will is free and it is the freedom of his will that makes it possible for him to elevate himself above his primitive animal desires. Man, unlike the lower creatures, is able, by means of his will, to reject the influences that threaten his existence and his development..."[18] In answer to the question of limits of human potential, Pestalozzi makes it clear that man has no limits, we are free to accept or reject was we wish, we do not have to believe what we do not wish.

IV. Theory of Learning: What is learning? How are knowledge and skills acquired?

Learning is what Pestalozzi was most out to change. In his time Pestalozzi noticed that learning in the classroom consisted primarily of reading out of texts and using rote memorization for songs, scripture, and psalms.[19] This is not the type of learning that Pestalozzi was in favor of; rather, he wanted children to be able to learn in a less restrictive setting. Pestalozzi wished to have the students learn by a hands-on approach, this means that given tools and a simple overview of what they will accomplish, students should be able to go out and gather information to come up with answers of their own. Children shouldn't be given answers but instead they should arrive at answers themselves.[20] Rather than having knowledge that was primarily verbal (artificial), Pestalozzi saw that knowledge that led to efficiency in useful doing (practical) was of real use to humans.[21] Pestalozzi saw society as a

group of individuals who lived together and helped one another.

Furthermore, Pestalozzi said that humans cannot live without the help of

our fellowmen, also that with the help of society we can be guided and

helped in accomplishing what we need to.27 [26]

As humans we are social beings who live with other social beings, this is

what makes a society.

>The institution that Pestalozzi saw as being involved in the education process first and foremost is the family. He said that of all institutions in society, family was the one that was nearest to his true ideal of education.28 26] This is so because Pestalozzi believed that the immediate environment in a child's life is what had the most influence on the child and what they were to learn in life, therefore, the child's home life is the most important institution in furthering the child's education.

"From the near to the far". This is what

Pestalozzi said in regards to who should be educated and schooled. What

he meant by this was that all men from any economic background should be

educated.29 Smith,

In addition, Pestalozzi believed that children of both sexes,

whether they be poor or orphans should also be educated as long as they

were at least five years of age.30 [26]

FOOTNOTES

[1]Mark Smith, www.infed.org/thinkers/et-pest.htm. (8 May 1997), 12 February 2008.

[2]

http://www.history.com/encyclopedia.do?printable=true&articleid=219037.

12 February 2008.

Smith

[3] N/A .

[4] N/A .

[5] N/A .

[6] N/A .

[7] Robert B. Downs, Heinrich Pestalozzi: Father of Modern Pedagogy (Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1975), 50

[8] N/A .

[9] N/A .

[10]N/A .

[11] Smith, ibid.

[12] Michael Heafford, <em>Pestalozzi: His Thought and Its Relevance Today</em> (London: Methuen & Co Ltd, 1967), 52.

[13] Heafford, 53.

[14] Downs, 57. Downs, 63.

[15] N/A .

[16] Walch, 91.

[18]

Heafford, 40.

Sister Mary Romana Walch, M.A., Pestalozzi and the Pestalozzian

Theory of Education (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of

America Press, 1952), 90. 1 Walch, 110.

[19] Gerald Lee Gutek, Pestalozzi & Education (New York: Random House, 1968), 102.

[20] N/A .

[21] Smith 21 Gutek, 105.

[22] Walch, 58.

[23]Downs, 89.

[24] Heafford, 77.

[25] Downs, 85.

[26] Downs, 39

26 Gutek, 110.

[27] Gutek, Gerald Lee. Pestalozzi & Education. Loyola University, Chicago: Random House, 1968, 94

[28] Heafford, Michael. Pestalozzi: His Thought and Its Relevance Today. London: Methuen & Co Ltd, 1967.

[29] Smith, Mark. Educational Thinkers. 8 May 1997.12 February 2008 at www.infed.org/thinkers/et-pest.htm.

[30] Walch, 51

[31] Walch, 169.

[32] Walch, 170.