The Educational Theory of Mohandas Gandhi

|

Analysts: |

|

©2000 NewFoundations

The Educational Theory of Mohandas Gandhi

|

Analysts: |

|

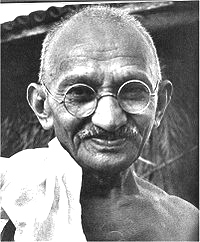

Mohandas Gandhi was "a great thinker in beggar's garb," an activist whose method of social reform was simultaneously radical, novel, and timelessly simple (Gutek, Gerald, 1997, pg. 351-367). The socio-cultural context in which Gandhi lived and worked made his method of enacting change uniquely powerful; in one of the most populated nations on the planet, at a time when world conflicts were raging, Gandhi used peaceful means to affect a revolution of cultural and political change for the Indian nation that resonated around the world. His experience in South Africa not only changed his outlook on politics but also helped him to see the role education played in that struggle (Garse, Sharma, 2010.)

In order to understand Gandhi's contributions to education it is important to understand "The Great Soul" in his full context of time and place in the world. What Gandhi did in word and deed was much like a pebble dropped into a still pond; his views on human rights and cultural dignity reverberate still among social activists, and his approach to civil unrest was duplicated by many contemporary leaders.

In order to break Dutch control of the spice trade, Britain established the British East India Company in the 1600s; over the next three-hundred years Britain assimilated and gained control over Indian infrastructure, from its roads and economy to its deepest social structures (www.iloveindia.com.) For a century and a half, India was ruled by the British East India Company, a trade group of merchants incorporated and given monopoly privileges on all trade with the Indies. Beginning as emissaries of King James I in 1615, the Company established massive trading posts in cities such as Madras, Calcutta and Bombay and was gradually transformed from a trading venture to a ruling enterprise (Lal, 1997).

British expansion in India grew, and the native people were subjected to the whims of the British colonialism that involved a strict system of monopolization to afford greater profits for the English. But around the turn of the Nineteenth century the move towards Indian independence began to gather steam. The leader and embodiment of this movement eventually came to be Mohandas Gandhi.

By 1920, Gandhi had become the prominent leader of the Indian National Congress, a thirty-five year old group lobbying for independence. For the next few years, his non-violent protests and boycotts of British policies and products involving thousands of people made enormous waves. The English authorities were not quite sure how to deal with Gandhi, because the people of India revered him. For instance, in March 1930 Gandhi implemented his most famous incidents of satyagraha, or peaceful coercion, the Salt March. Thousands hiked more than 200 miles with him to the sea where together they made salt - a product monopolized by the British and deemed illegal to make or sell otherwise. Gandhi believed that such actions were not intended to embarrass the wrongdoer (the British) but rather to convert their motives so that they act from a new understanding (Nanda, B., 2010).

Gandhi preached passive resistance, believing that acts of violence against the British only provoked a negative reaction whereas passive resistance provoked the British into doing something. To Gandhi, non-cooperation was not a passive state, but an intensely active one that held the promise of the conquest of the adversary by personal suffering. (Nanda, B., 2010)

Historically, India is a nation at the confluence of many religions: Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism, and Islam. Today, while Hindu, Jain and Buddhism are considered the ancient religions, almost 80% of Indians are Hindu, and 12% practice Islam (Aharon, D., 1998)

In India the word ådharma is used to mean åreligion, but it should be noted that in Hinduism ådharma has a much wider connotation. The word ådharma comes from the root ådhre, which means åto sustain. åDharma is thus the greatest sustaining force or the binding force of the society. The goal of ådharma is to create mental and spiritual fellowship among all men and to regulate its relation with all living entities. Any religion, any custom, any creed could be brought under its fold. Gandhi's dharmic concept of religion, therefore, brought under its fold people belonging to different religions (Kamat, K., 1996).

Though born Jain, Gandhi practiced Hinduism, and used his faith as his staff; he relied greatly on the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita, and credited the ancient text as being the source of his understanding of dharmic philosophy. The Gita, or åuniversal mother as Gandhi referred to it, is a Hindu poem involving the god Krishna and a warrior disciple. It was the Krishna of the Bhagavad Gita that Gandhi saw as wisdom personified, and the dialogue of Krishna that Gandhi used as an everyday guide to life. (Kamat, K., 1996).

Gandhi read the Bible while he was a law student in England, and the life of Christ and the Sermon on the Mount went straight to his heart. Gandhi described Jesus as the

"òhellip; the greatest passive resister the world has ever seen" (Wofford, H., 1955), and the words of the Sermon infused his thinking. The idea of returning love for hatred and good for evil, to åturn the other cheek. captivated him. In fact, years later Dr. Martin Luther King also cited the messages of the Sermon on the Mount as a guiding resource (Lecture 25, www.wfu.edu/~matthetl/perspectives/twentysix.html).

Raised by a devout mother in the Jain traditions of the region, Gandhi observed early the influences that would play an important role in his adult life including vegetarianism, fasting for self purification, and mutual tolerance between individuals of different creeds (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohandas_Karamchand_Gandhi). It is believed that Jainism is one the worlds oldest religions, predating Hinduism; the main tenets of Jainism are five basic ethical principles, or vows: non-violence, truth, non-stealing, celibacy and non-possession (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/jainism). .

Gandhi, in his later writings, described himself as a Hindu and stated "Hinduismòhellip;entirely satisfies my soul, and fills my whole being." (Harijan, 1937) Gandhi used his devout Hindu beliefs as a bridge to understanding other religions and finding the universal constants that underlie most belief systems. For instance, Gandhi's interest in Christianity was leavened with his Hindu perspective. "I regard Jesus as a great teacher of humanity, but ... God cannot be the exclusive Father and I cannot ascribe exclusive divinity to Jesus" (Harijan, 1937).

Gandhi was born in 1862 in Porbandar, a small town on the Western coast of India. His father, Karamchand Gandhi, was the diwan (Prime Minister) of Porbandar state, a small princely state of British India. Married at 13, and educated as a lawyer in England, Gandhi quickly turned his legal experience and his colonial education into an opportunity to be an agent for social transformation (Garse, Sharma, 2010). In London, Gandhi joined the Vegetarian Society and became intrigued with religious thought and became fascinated with studying Christian scripture (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohandas_Karamchand_Gandhi).

Gandhi was called to the bar in June, 1891, and left London for India. He failed to establish a law practice in India on his own because, in Gandhi's own words, he "hated public speaking and was not very good at court appearances." (Ghosh, S. 2003) Gandhi was forced to close a business of drafting petitions for litigants when he ran afoul of a British officer. In April, 1893, he accepted an offer for a post in the colony of Natal, South Africa, then part of the British Empire (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohandas_Karamchand_Gandhi).

In South Africa, Gandhi faced discrimination directed at Indians. This was a turning point in his life, awakening him to social injustice and influencing his subsequent social activism. It was through witnessing first-hand the racism, prejudice, and injustice against Indians in South Africa that Gandhi started to question his peoples status within the British Empire and his own place in society (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohandas_Karamchand_Gandhi).

With his colonial education Gandhi had a unique perspective on the issues facing British dominion of Indian society. Schooled in the British way and from their perspective, Gandhi understood the depth of oppression that Indians would suffer if they could not eventually break free of British rule. Passive resistance, or ahisma, was Gandhi's method of protest, and it was this radical and approach to opposing oppression that ultimately paved the way for Indian independence (Garse, Sharma, 2010).

Under British dominion, formerly self-sufficient Indian villages came to rely on British goods and services and the deeply ingrained social caste system became even more divisive. Educationally, village India remained illiterate and ignored, as the British language and western attitudes were introduced to the educated Indian elite (Garse, Sharma, 2010).

Gandhi's dissatisfaction with what he perceived as social injustice caused him to examine the flaws in the social, educational, financial, and political systems at work in his world. The rigid caste system in India had, for generations, vilified physical labor in favor of intellectual work; physical labor was relegated to the lower caste only. Once British rule took over, education in India further moved from a moral/physical emphasis to an intellectual one. Gandhi realized that, in order for substantive change to come to his people, cultivation of the individual would have to be thorough and integrative, and that physical skills would have to be taught. (Garse, Sharma, 2010).

His reputation as a true nationalist as well as an internationalist is very obvious. In the academic sense, he is not considered a great scholar or an educational theorist. Gandhi has not expressed directly his views on education or on the problems related to it, through any particular book. There is no special research article available, which could have given us a glimpse of his ideas or suggestions on the education system (www.gandhifoundation.net, 2010).

Gandhi openly credited three people as sources of inspiration and guidance: Raychandbhai by his living contact; Tolstoy by his book, "The Kingdom of God Is Within You"; and Ruskin by his "Unto This Last." Besides these three personalities, the Bhagavad Gita and the Bible texts were life long resources for him. (Garse, Sharma, 2010)

Shri Raychandbhai was a businessman whom Gandhi met on his return to India from London. Gandhi found his new friend to be of great character and learning, and throughout his life the two men were mutual confidants (Garse, Sharma, 2010).

Gandhi read Ruskin's Unto The Last, and said, "I could not get any sleep that night. I was determined to change my life in accordance with the ideals of the book." He later translated the book and called it Sarvodaya (the well-being of all). Ruskin's book influenced Gandhi's concept of åsoul-force as a substitute for physical force and changed him as a person. It brought "an instantaneous and practical transformation" in his life. From Ruskin, Gandhi learned that the good of the individual is contained in the good of all; that the lawyer's work has the same value as the barber; that all have the same right of earning their livelihood; that the life of labor as a tiller of soil or the craftsman, is the life worth living (Shuthka, N., 2002).

The most public figure with whom Gandhi established a rapport was the Russian novelist and thinker Leo Tolstoy. Tolstoy, forty-one years Gandhi's senior, was well known for his novels Anna Karenina and War and Peace. It was his spiritual writing, The Kingdom of God is Within You that Gandhi found inspirational. In the preface to The Kingdom of God is Within You, Tolstoy specifically states that his intent is to examine the notion of non-resistance to evil by force. (Tolstoy, L. 1893).

In 1909, Gandhi had read in a local newspaper Tolstoys Letter to a Hindu, a letter to Indian revolutionary Tarak Nas published in the Free Hindustan. In the letter, Tolstoy counsels non-aggression, stating, "[When Indians] seek liberation from subjection to the Englishòhellip; one thing only is needfulòhellip; the law of love, which brings the highest happiness to every individual as well as to all mankind." A response to this letter led Gandhi to establish a correspondence with Tolstoy. (Tolstoy, L., 1893)

Gandhi and Tolstoy had much in common; in later years they both were considered prophets of their respective time, society and culture. Tolstoys ideas about renouncing force as a means of opposition were akin to Gandhi's own thoughts, although he did not share Tolstoy's intense dislike for organized government. (Bhana, S., 1975) Tolstoy manifested independent thinking, profound morality and truthfulness, and his ideals of 'resist not evil' and nonviolence struck deep chords with Gandhi. Gandhi began to mould his life according to the ideas of Tolstoy. (Shuthka, N., 2002)

Gandhi wrestled with the conflicting yet similar messages of Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Sikhism - all of these religions had elements Gandhi understood as well as principles he could not accept. For instance, Gandhi questioned the claim that Jesus was the only son of God. "If God could have sons, all of us [are] his sons." (Gandhi, M.K., p. 136)

Such profound religious consideration on Gandhi's part resulted in his establishing two communities where he attempted to put his religious, social and political philosophies to work. In 1904, he established the Phoenix Settlement in the Natal province of South Africa based on Ruskins writings; in 1908, he established the Tolstoy Farm just outside of the South African capital of Johannesburg. These family farms, or ashrams, allowed Gandhi to experiment with the kind of communal living that he had seen in 1895 among Trappist monks. (Bhana, S. 1975)

Tolstoy Farm consisted of men, women and children for long, short, and irregular intervals, who were Hindu, Muslim, Christian or Parsee, white or Indian; who spoke Hindi, Tamil, and English. There were around 40 young men, 2 or 3 åold men, 5 women, and 20 to 30 children. The ashram was a heterogeneous microcosm in which his leadership would prepare him for his role in the political macrocosm of India. (Bhana, S., 1975).

As Gandhi explored and refined the practical application of his philosophy, his concept (and perhaps most significant social contribution) of satyagraha was developed. Simply put, satyagraha is a method for resolving conflict. Focusing on conflict resolution, Gandhi thought, would "...liquidate antagonisms, but not the antagonists themselves." (Easwaran, E.,pg. 155). Satyagraha became the underpinning for many social reformation movements, and was specifically cited by Dr. Martin Luther King in a 1959 speech:

"I am convinced that the method of non-violent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom and human dignity." (www.mlkonline.com)

I: The Theory of Value

What knowledge and skills are worthwhile learning?

Gandhi put immense emphasis on moral and ethical knowledge. According to him, an educational system that lacked these two could not be termed as good. The reason behind such a thought was that without morality and ethics, no student, in a real sense, can be considered healthy in mental and physical terms. Spiritual growth, described by Gandhi as an essential part of education, can only be attained through learning morality and ethics. On the one hand where students should gain education under the strict regimen of high morals, self-control, and right thinking, on the other, they should also be expected to provide service to the society in general. (Kumar, R., 2008)

One component of spiritual training that Gandhi valued was physical work and vocational training; these disciplines allow individuals to shed reliance on others and develop intellectually, spiritually, and physically. (Garse, Sharma, 2010) Gandhi believed the universe was subject to unalterable laws that "òhellip;govern everything and every being that exists or lives." (Chattopadhaya, K., 1986) Human beings, then, needed to cultivate the mind, body, and heart in a harmonious manner; only then, Gandhi believed, could change come to the immoral political and social conditions that violated the spiritual dignity of individuals (Chattopadhaya, K. 1986)

According to Gandhi, the skills that were worthwhile learning were handicrafts, literacy, and the acquisition of knowledge. He was opposed to modern machinery, saying:

"Knowledge of the production processes involving crafts such as spinning, weaving, leatherwork, pottery, metal work, basket making, and bookbinding have been the monopoly of specific caste groups in the lowest stratum of the traditional social hierarchy." (Burke, 2000)

Gandhi felt that people were not workers but slaves if they worked with modern machinery, and instead referred to it as contributing factor to the impoverishment of India. Gandhi maintained that, "if machinery craze grows in our country, it will become an unhappy land." (Burke, 2000)

For instance, the manufacture of clothing was a critically important skill to many Indian villages; beginning with the cultivation of the cotton crop, its harvesting, and ultimate weaving into fabric, such steps provided an education that was both active and useful. Gandhi believed that such craft education satisfied a basic human need and provided "purposeful, creative, and socially useful education." (Gandhi, M.K., 1947)

What are the goals of education?

In his own words, Gandhi felt that

"...under ideal conditions, true education can only be imparted by the parents...with a minimum of outside help." (Gandhi, M.K. 1957)

Gandhi experimented with educational concepts during his time at the Tolstoy Farm ashram in South Africa. Viewing the Tolstoy ashram as a "family" farm, Gandhi viewed himself as the "father" responsible for the education of all children living there. His main goal as "paterfamilias" was to build a firm character in the children, in the expectation that a sound foundation would allow them to further learn what they needed from others (Gandhi, M.K., 1957)

Gandhi felt that the goals of education were to develop and prepare Indians for society. Given Gandhi's values and his vision of what constituted a truly civilized and free India, it was not surprising that he developed firm views on education. Gandhi believed that education not only moulds the new generation, but also reflects a societys fundamental assumptions about itself and the individuals that compose it. (Burke, 2000)

Gandhi's experiences in South Africa not only changed his outlook on politics, but also helped him see the role that education played in that struggle. He became so opposed to all aspects of English education that he consistently referred to it as "rotten." (Burke, 2000)

In order to strengthen morality and ethics in students, Gandhi advocated the introduction of religious education. He believed that this kind of education brought the values of forbearance, tolerance, and reverence in ones character. In turn, these values are an indivisible part of ethics. Explaining the importance and need of religious education, Gandhi wrote in "Young India" in December, 1923,

"a curriculum of religious instructions should include a study of the tenets of faith other than ones own. For this purpose, the students should be trained to cultivate the habit of understanding and appreciating the doctrine of various religions in the world in a spirit of reverence and broad-minded tolerance." (Kumar, R., 2008)

While Gandhi's main contributions are often identified as political and spiritual, his philosophy for a basic education was based upon the goal of freeing India from colonial domination. By empowering the individual spiritually, physically, and intellectually, Gandhi felt that collective India would become stronger. By cultivating an appreciation for physical labor, Gandhi hoped to free his people from a stigma of oppression and reliance on outsiders for survival. With these tools, the people of India would be able to be morally resistant to foreign domination, and be better prepared to self-govern and sustain their society (Gandhi, M.K., 1947)

II: Theory of Knowledge

What is knowledge?

"It is unwise to be too sure of ones one wisdom. It is healthy to be reminded that the strongest might weaken and the wisest might err." -- M.K. Gandhi

Gandhi was explicit in his writings and actions about what he believed to be "knowledge," and was even credited with having identified "knowledge without character" as one of the seven human blunders that cause violence in the world. More specifically, Gandhi stated, "...knowledge includes all training that is useful for the service of mankind." (Gandhi, M.K. 2010)

Moral and ethical knowledge is the first point on which Gandhi's concept of value education is based. Gandhi believed that any education that lacked these two elements could not be considered adequate. Gandhi reasoned that without morality and without ethics, no student in a real sense could be considered healthy in mental or physical terms. A person who is not a moralist and who does not differentiate between right or wrong cannot rise to the essential level of a true student. (Kumar, R., 2008) For instance, knowledge was the learning of crafts, subjects in school, and being self-sufficient. Gandhi felt it was important to learn a craft such as weaving, without the influence of modern machinery. (Burke, 2000)

Gandhi proposed the introduction of productive handicrafts into the school system because what he really wanted was for the schools to be as self-supporting as possible. There were two reasons for this: first, a poor society such as India simply could not afford to provide education for all children unless the schools could generate resources from within. Secondly, the more financially independent the schools were, the more politically independent they could be. Gandhi wanted to avoid dependence on the state that he felt would mean interference from the central government. (Burke, 2000) Above all else, Gandhi valued self-sufficiency and autonomy. These were vital for his vision of an independent India made up of autonomous village communities to survive.

How is knowledge different from belief?

It is difficult to separate belief from knowledge in studying Gandhi's philosophy, as the two concepts were unquestionably intertwined. In Chapter XVIII of the Hind Swaraj (Gandhi, M.K., 1909), Gandhi definitively stated his definition of education:

"The person who is properly educated whose body is the ready servant of his will; whose intellect is clear; whose mind is stored with a knowledge of the fundamental truths of nature." (Gandhi, M.K., 1909)

Braided into Gandhi's view of education was the necessary spiritual foundation to ensure the success of education.

"A proper and all-around [education] can take place only when it proceedsòhellip;with theòhellip; spiritual faculties of the child." (Gandhi, M. K., 2010)

Gandhi is described as a holistic, pragmatic, idealistic, and farsighted educational reformer. While his agenda for education has all but been abandoned in India today, his spirit and ideals remain perennially relevant to many cultures and societies dealing with social change. (Gandhi, M.K., 2010) In his autobiography, Gandhi wrote that "truth" was the sovereign principle that governed his actions and by which he was eternally bound. Thus, "truth" was his prime belief, the underpinning of all precepts Gandhi wrote, spoke, and acted on. "The truth is not only truthfulness in word," Gandhi wrote, "but truthfulness in thought also."(Burke, 2000)

What is a mistake? A lie?

Gandhi's lifelong quest for the truth was the lens through which he made his observations on mistakes and lies. In a conversation with his grandson, Arun Gandhi described what he believed were seven "blunders," or mistakes, mankind commits that cause violence in the world: Wealth without work; Pleasure without conscience; Knowledge without character; Commerce without morality; Science without humanity; Worship without sacrifice; and Politics without principles. Arun later added an eighth mistake: Rights without responsibility.

These mistakes, as abbreviated by Gandhi, have been used and reused in contemporary culture and literature. In fact, the best seller Seven Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey is based on Gandhi's seven principles with a contemporary twist. Covey lists Gandhi as one of his personal heroes (Covey, S., 2010) and lists as one of his own mission statements Gandhi's comment, "I shall conquer untruth by truth."

III: Theory of Knowledge

What is a human being?

"You must not lose faith in humanity. Humanity is an ocean; if a few drops of the ocean are dirty, the ocean does not become dirty." - Mahatma Gandhi

Gandhi saw humanity as an indivisible, organic whole, tied together by the expectation that every man is responsible to and for others and to be deeply concerned about how others lived (Parekh, B., 2010) Gandhi had a clear understanding of the interdependence of human beings and the ways in which the behaviors of oppression and domination were maintained (Parekh, B., 2010)

With this view of the human "whole," Gandhi made the argument that every human action simultaneously affects the welfare of both the collective society and the individual. This implied, Gandhi felt, that no man could injure another without inflicting it on himself as well. "To slight a single human being," Gandhi said, "is to harm not only that human but with him the whole world" (Parekh, B., 2010)

How does it differ from other species?

Gandhi gave much thought to the idealized human being. In his reflections on the main Hindu spiritual text, the Bhagavad-Gita, Gandhi recognized the qualities by which the "perfected man" could be identified (Gandhi, 1988) In "The Message of the Gita," Gandhi wrote, "All embodied life is in reality an incarnation of God," and went on to explore the philosophical implications of mankinds ability to embody God-like qualities (Gandhi, 1988)

Gandhi went on to further explore the eternal struggles faced by mankind as living beings. In his autobiography, Gandhi stated that while man in his primal state knows no self-restraint, civilized man is different because he is capable of self-restraint (Iyer, R., 2010, Gandhi, 1962)

Gandhi wanted to impress upon his countrymen the value of their ancient culture. For example, one of Gandhi's most subtle yet powerful acts was to begin the liberation of the lower castes. Once called "those who cannot be touched," Gandhi began to call this outcast group Harijans, or Children of God. His message to his own people, and to the British imperialists as well, was that "when you weaken others, you weaken yourselves, and weaken the entire nation" (Eswaran, E., 1997)

This perspective also formed Gandhi's criticism of the subjugation of individuals and societies. Gandhi argued that social domination rested on simple misunderstandings of human nature, and that every human being owed to others his full share of collective responsibilities (Parekh, B., 2010)

What are the limits of human potential?

Gandhi's thoughts surpassed his time and culture, echoing on to inspire new generations of social activists around the world. In the 1960s Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said of Gandhi, "If humanity is to progress, Gandhi is inescapable. He lived, thought, and acted, inspired by the vision of humanity evolving toward a world of peace and harmony. We may ignore him at our own risk" (www.Gandhi'serve.org). At the turn of this century a more contemporary voice, HH The Dalai Lama, similarly embraced Gandhian philosophies. "He made every effort to encourage the full development of the positive aspects of the human potentialòhellip;it is my prayer that, as we enter this new century, nonviolence and dialogue will increasingly come to govern all human relations" (www.Gandhi'serve.org).

While many thought that only Indias freedom was the main goal of Gandhi's life work, the larger view shows that his philosophy and his actions were rooted in Gandhi's belief in the unity of human life. Gandhi's view of humanity as "the synthetic whole" meant that it could not be made divisible into spheres like social, religious, political, moral or ethical nor classified in levels like individual or collective, local or international. Instead Gandhi viewed society through the principle of ådharma, a contiguous whole bound by the sustaining force of the society. (Kumar, R., 2007)

IV: Theory of Learning

"Persistent questioning and healthy inquisitiveness are the first for acquiring learning of any kind." - Gandhi

Gandhi felt that learning included the acquisition of information and training that is useful for the service of mankind; specifically, the core of Gandhi's educational proposals was the introduction of productive handicrafts in the school curriculum. The idea was not simply to introduce handicrafts as a compulsory school subject but to make the learning of a craft the centerpiece of the entire teaching program. Gandhi's proposal intended to stand the education system on its head. The social philosophy and the curriculum of what he called "basic education" thus favored the child belonging to the lowest stratum of society, thus implying a transformation of social perception. (Burke, 2000)

How are skills and knowledge acquired?

Gandhi's concept of basic education was concerned with learning that was generated within everyday life, such as schools based on productive work for the benefit of all. It was also an education focused on the individual but reliant on cooperation between individuals. (Burke, 2000)

According to Gandhi, the skills that were worthwhile learning would enable a poor society such as India to become first financially independent, then politically independent. Above all else, Gandhi valued self-sufficiency and autonomy; these were vital to his vision of an independent India made up of autonomous village communities.

Gandhi wanted to free the Indian teacher from interference from outside, particularly from government or state bureaucracy. Under colonial rule the teacher had a prescribed job to do that was based on what the authorities wanted the children to learn. Gandhi, instead, saw basic education as the embodiment of his perception of an ideal society consisting of small, self-reliant communities with his ideal citizen being an industrious, self-respecting and generous individual living in a small, cooperative community. (Burke, 2000)

V: Theory of Transmission

Who is to teach?

The right to autonomy that Gandhi's educational plan assigns to the teacher in the context of schools daily curriculum is consistent with the libertarian principles he shared with Leo Tolstoy. Gandhi wanted to free the Indian teacher from the slavery of the bureaucracy. The schoolteachers job had come to be defined under colonial rule as one transmitting and elucidating the forms and content of knowledge selected by bureaucratic authorities for inclusion in the prescribed textbooks. Gandhi wrote,

..."if textbooks are treated as a vehicle for education, the living word of the teacher has very little value. A teacher who teaches from textbooks does not impart originality to his pupils." (Kumar, K., 1999)

Gandhi's basic education plan implied the end of the teachers subservience to the prescribed textbook, and the curriculum. More important, however, was the freedom and authority that the basic education plans gave to the teacher in matters concerning the curriculum. It was a libertarian plan inasmuch as it denied the State the power to decide precisely what the teacher must do in the classroom. In accordance with his wider philosophy of social life and politics, this aspect of Gandhi's educational plan implied a dramatic reduction of the States sphere of authority. (Gutek, G., 1997, p. 363)

By what methods? What will the curriculum be?

In expressing his educational philosophy, Gandhi defined education as the "all-round drawing out of the best in child and man- body, mind and spirit." Gandhi in India of My Dreams, expressed his vision of the new India:

"I hold that the true education of the intellect can only come through a proper exercise and training of the bodily organs, e.g. hands, feet, ears, nose, etc. In other words, an intelligent use of the bodily organs in a child provides the best and the quickest way of developing his intellect. But unless the development of the mind and body goes hand in hand with a corresponding awakening of the soul, the former alone would prove to be a poor lop-sided affair. By spiritual training I mean education of the heart. A proper and all-round development of the mind, therefore, can take place only when it proceedsòhellip; with the education of the physical and spiritual faculties of the child. They constitute an indivisible whole. (Gutek, 1997, p. 363)

For Gandhi, an education that integrated and harmonized the human faculties should be craft centered. Gandhi said he would "begin the childs education by teaching it a useful craft and enabling it to produce from the moment it begins its training." Accordingly, in Gandhi's plan for basic education, primary schooling was compulsory for all children between the ages of seven and fourteen and conducted in the childs own language. The craft used in the particular school was to be one of the major occupations found in India and all the instruction was to be correlated to the particular craft. Further, Gandhi believed that the sale of the items produced in the schools would make education productive and self-supporting. (Gutek, 1997, p. 364)

Gandhi's philosophy of basic education was also an element in his design for a new India. Like other social reformers, Gandhi saw education as a method of social reconstruction that would improve both individuals and their society. By involving the child as a participant in an interacting educational and productive group, basic education would counteract the ingrained Indian attitude that relegated physical labor to lower castes and also the modern tendency to antisocial individualism. (Gutek, 1997, p. 364)

Basic education, according to Gandhi, would inculcate a spirit of cooperation, unity, and group responsibility. Gandhi conceived of the school as a miniature society where children as social participants had rights and responsibilities. Gandhi saw basic education as providing a common educational foundation that would reduce the gap between urban and rural India. He said, "Craft education will provide a healthy and moral basis of relationship between the city and the village and thus go a long way towards eradicating some of the worst evils of the present social insecurity and poisoned relationship between the classes". (Gutek, 1997, p. 364)

VI: Theory of Society

What is society?

Gandhi was direct in his rejection of Western or "modern" civilization, and extended his rejection to encompass those elements that are commonly considered "social progress." (Burke, 2000) Specifically, Gandhi took issue with which could be summed up in two axioms embraced by Western culture: "might is right" and "survival of the fittest." (Heredia, R., 1999) Instead, Gandhi felt that being civilized meant humans acting in a way that led to duty, a concept in contrast to his understanding of Western values. As set forth by Gandhi, this position opened up a series of "ethical issues" between the colonizer and the colonized, the dominant and the dominated, the oppressor and the oppressed.

Gandhi was gifted in imbuing spirituality into understanding the mechanics of social operation. For instance, in his book Hind Swaraj, Gandhi defines civilization in the context of a disease, and states, "The true test [of civilization] lies in the fact that people living in it make bodily [comforts] the object of life." In the same text, Gandhi rails against his perception of European "civilization," going so far as to call it "satanic." (Gandhi, 1909)

What institutions are involved in the educational process?

Gandhi felt that a Western education was a "false education," one that did not comport with his belief that being "civilized" is enabling one to do their duty. (Gandhi, 1909)Gandhi claimed that he had freed himself of the ill effects of his own "false education" and in so doing illustrated its "rottenness."

In Hind Swaraj, Gandhi makes the argument that Indians receiving an English education has "enslaved a nation." Gandhi illustrates this point in a simple yet powerful irony - though the concept of "swaraj" is to establish home rule in India, it was largely disseminated and discussed in English. (Gandhi, 1909)

Gandhi goes on to specifically identify segments of education that he felt defeated his vision of home rule, and spoke strongly on the corruption of Indian education. For instance, he called religious educators "hypocritical and selfish." Language was also problematic; those Indians whose education was English "have enslaved India; the curse of the nation will rest not upon the English but upon us." (Gandhi, 1909)

VII. Theory of Opportunity

Who is to be educated? Who is to be schooled?

There will have to be rigid and iron discipline before we achieve anything great and enduring, and that discipline will not come by mere academic argument and appeal to reason and logic. Discipline is learnt in the school of adversity - M. K. Gandhi

It is important to note the distinction between åeducation and åschooling. While Gandhi wanted his Tolstoy Farm ashram experiments to be models of åeducation, he ventured into curriculum models in more formal åschooling arrangements. For example, Gandhi said that education at Tolstoy Farm should concern itself with the "culture of the heart or the building of the character." However, he was more specific about schooling, stating that the Tolstoy programs taught "manual and mental training," such as gardening, farming, and the like. (Bhana, S., 1975)

Gandhi's social philosophy and ideas on a basic education favored the child belonging to the lowest stratum of society. In so doing, Gandhi was able to promote a social transformation by altering the symbolic meaning of education and thereby changing the established structure of opportunities for education.

Tolstoy Farm allowed Gandhi the chance to experiment with implementation of his ideas on education and schooling. Called a "heterogeneous microcosm," the Farm worked on the basic premise Gandhi believed that "òhellip;it should be an essential of read education that a child should learn to conquer hate by love, untruth by truth, and violence by self-sacrifice." Gandhi's goals in education of young minds were similar to his insistence on what adults should strive for in their lives. (Bhana, S., 1975)

VIII. Theory of Consensus

Why do people disagree? How is consensus achieved? Whose opinion takes precedence?

In 1906, Gandhi decided to find a new term for his method of engaging in conflict. He invited readers of his journal, Indian Opinion, to offer suggestions, and he offered a book prize for the winning entry. The one that most intrigued him came from his own cousin, Maganlal, which Gandhi refined into the term, Satyagraha.

What Gandhi found appealing about the winning phrase was its focus on truth. He reasoned that no one possesses a complete view of it. The very existence of a conflict indicates a deep difference over what is right. The first task of a conflict, then, is to try to see the conflict from both sides of an issue. This requires an effort to understand an opponents position as well as ones own.

The ability to cast an empathetic eye was central to Gandhi's view of conflict. It made it possible to imagine a solution that both sides could accept, at least in part- though he also recognized that sometimes the other side had very little worth respecting. In his campaign for the British to åquit India for instance, he regarded the only righteous place for the British to be was Britain. Yet at the same time, he openly appreciated the many positive things that British rule had brought to the Indian subcontinent, from roads to administrative offices. (Gangal, A, Abstract pg.6)

Gandhi believed that all power resided in the people and that it should also originate from the people. The dynamo of power in a country like India should be the village. The village was to be a knot in a system of oceanic circles in which the remotest circle derived its strength from the center, i.e., the individual. This would mean that sovereignty was not to remain concentrated at any one level. It was to be diffused among units rising horizontally, till they reached the national level. In terms of political science, the residuary power remained in the village and the center was there to co-ordinate the work. Gandhi believed in Thoreaus saying, "that government is the best which governs the least". (Pandikattu, K. 2000 pg.24)

Since the majority rule violated the moral integrity of the minority and since unanimity was often impossible, all decisions in a non-violent society should be based on consensus, arrived at by rational discussion in which each strove to look at the subject in question from the standpoint of others. (http://library.thinkquest.org)

1. Parekh, Bhiku. Gandhi's Legacy. Pushpanjali: Essays on Gandhian Themes. Excerpted March 2010 from http://www.gandhi-manibhavan.org/activities/essay_gandhilegacy.html

2. M. K. Gandhi, The Message of the Gita. Appendix, The Bhagavad-Gita, A New Translation, S. Mitchell, 1988.

3. Iyer, Rhagavan. Gandhi's View of Man and History. Manas Report, 1962. Vol. XV, No. 33. Excerpted March 2010 from http://www.manasjournal.org/pdf_library/VolumeXV_1962/XV-33.pdf

4. E. Eswaran, E. Gandhi, The Man: The Story of his Transformation.1997

5. Gandhi'serve Foundation. Others On Gandhi. Mahatma Gandhi Research and Media Service. Excerpted March 2010 from http://www.Gandhi'serve.org/information/others_on_gandhi/others_on_gandhi.html

6. Kumar, Ravindra. Remembering Gandhi on the 60th Anniversary of Indias Independence. October 9, 2007. Excerpted March 2010 from http://www.globalpolitician.com/23579-gandhi

7. Gutek, Gerald. Historical and Philosophical Foundation of Education: A Biographical Introduction. 2nd Ed. 1997.pp.351-367

8. Garse, P. and Sharma, S. Ghandis Views on Youth as an Agent for Social Transformation. Mumbai University. Excerpted from Gandhi, M.K. Excerpted from Mahatma Gandhi. One Spot Information, http://www.mkgandhi-sarvodaya.org.

9. Gandhi, M.K. India of My Dreams. 1947. Excerpted February 2010 from The Encyclopedia of Informal Education, www.infed.org/thinkers/et-gand.html

10. OLPC Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. (n.d.). Retrieved from the OLPC Wiki http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohandas_Karamchand_Gandhi

11. Burke, Barry (November 4, 2009). Mahatma Gandhi on education Retrieved from www.infed.org

12. Gandhi, M.K. An Autobiography: The Story of my Experiments with Truth. 1957. pp333-335.

13. Chattopadhaya, K. 1986. Quoted from "Inner Recesses, Outer spaces" Excerpted February 2010 from http://www.kamat.com//mmgandhi/on_childrens_education.htm

14. Gandhi, M.K. Basic Education (Baniyadi Shiksha) from The Selected Works of Gandhi, UJG. Excerpted Feb 2010 from www.mkgandhi.in/edugandhibasic_1.html

15. Paragajue, M. The Relevance of Mahatma Gandhi's Educational Philosophy

16. Covey, S. The Community, Empowering Your Greatness, March 2000. Excerpted February 2010 from www.stephencovey.com

17.Ghosh, Shubha. (2003). Gandhi & The Life of the Law. Volume 53 November 4, 2003 http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/pop/etext/syracuse/ghosh.html

18. OLPC (n.d). Retrieved from the OLPC Wiki. http://En.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jainism

19. Zuideiveen, J. (2001. Colonial India, Gandhi and Eventual Independence www.wmich.edu/dialogues/themes/indiagandhi.html

20.Trueman, C. (2000). www.historylearningsite.co.uk/mahatmagandhi.html

21. Kumar, Ravindra Dr. (2008). Gandhian View on Morality and Ethics. Retrieved April 3, 2008, from www.globalpolitician.com

22. Burke, Barry (2000). Gandhi on Education: Excellent Collection of Quotes from the National Council for Teacher Education Mahatma Gandhi, Retrieved November 4,2009, from www.infed.org/thinkers/et-gand.htm#education

23. Harijan (1937). Hinduism & History of Gandhi. Retrieved April 1, 2010, from http://hinduism.about.com/od/history/a/gandhiquotes.html

24. Love of India. Retrieved on April 19, 2010 www.ILoveIndia.com

25. Ghosh, Shubha (2003). Gandhi & The Life of the Law [Electronic version] Volume 53 Number 4 http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/pop/etext/syracuse/ghosh.html

26. OLPC (n.d.) Retrieved from the OLPC Wiki http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jainism

27. Zuiderveen, Josh (2001) Colonial India, Gandhi and Eventual Independence Retrieved April 19 ,2010 from www.wmich.edu/dialogues/themes/indiagandhi.html

28. Trueman, Chris (2000) Mahatma Gandhi Retrieved April 4, 2010 from www.historylearningsite.co.uk/mahatma-gandhi.html

29. Tolstoy, L (1893). The Kingdom of God is within you. Retrieved from www.kingdomnow.org/w-inyou00.html

30. Bhana,S (1975). Tolstoy Farm. www.tolstoyfarm.com/thepast.html

31. Gandhi (1909). Swarajpeeth. www.swarajpeeth.org/swarci-dialogue-/46.html

32. Heredia (1999).www.swaraj.org/interepting.html