Fair Share vs. Fair Play:

Two Competing Conceptions of Justice

©1999 Gary K. Clabaugh

Ultimately, whether or not to track students is a question of justice, To illustrate, I once taught in a junior high where sections were ranked by ability. School policy also required that students in the two lowest sections receive nothing higher than a C. I was a new teacher and, at first, I thought these policies were fair. Then I taught Harry -- a pleasant fourteen year old who had been held back once. He was very slow and claimed to be a boy evangelist, though everyone knew he was no such thing. During study hall he wrote "sermons" he claimed he would deliver in a local sports arena. One on teenage Christians read, "Hi, my name is Harry and I am both a teenager and a Christian." I asked, "Is that the whole sermon Harry?" He replied, "Yep, that's it." When I said, "That's the kind of sermon I like, short and to the point," Harry thought I was serious.

To support his "evangelism" Harry sent for quantities of evangelical tracts that he never distributed. He told me that if he took them home, his mother threw them away. That so upset him that I let Harry store these pamphlets in the back of my room. That made me his friend for life.

Harry's father, a trash man, was notorious -- the town "clown." He had to be thrown out of local funeral homes, for example, because he insisted on mourning people whom he didn't know. And year after year he tried to lead the forth of July parade even though he had been warned not to even try to march. He even liked to startle motorists by jumping into their path from behind the trash truck. (The Chief of Police repeatedly warned Harry's dad that this was dangerous, but it didn't do any good.)

Harry's mother, a toothless woman who wore filthy clothes, was said by town folk to be a "nut case." That was a bit harsh, but when she attended a parent-teacher conference, I literally could not understand what she was trying to say to me. Non-sequiturs mingled with long pauses and pointless references to create a totally puzzling experience.

Despite what must have been a harrowing home life, Harry was as diligent as he was dull. If, for instance, his homework wasn't right the first time, Harry sought my help. If he got it wrong a second time, he was back for more help. And when he did catch on, which happened sporadically, Harry was elated. Sometimes he would also try to teach what he had learned to his slower classmates -- even when they didn't want to know.

By report card time it was obvious to me that Harry was making heroic efforts. And he was a model citizen in the bargain. No doubt about it, judged on effort, Harry deserved an A. Sadly, however, compared to my brightest students he deserved an F. What grade should I assign?

After much soul-searching I gave Harry an A. He was doing more with what he had than any other student. Besides, this was seventh grade and Harry's report card would count for little outside the school. Nevertheless, as soon as the principal saw Harry's report card he ordered me to change my grade. "School policy permits nothing higher than a C." he chided. I told him I was aware of the policy, but respectfully declined to change Harry's grade. I tried to explain why, but the principal interrupted, saying, "I'll change the grade myself!" He turned and started to walk out, then paused, laughed derisively, and said, "I guess it won't matter; everyone else gave him an F."

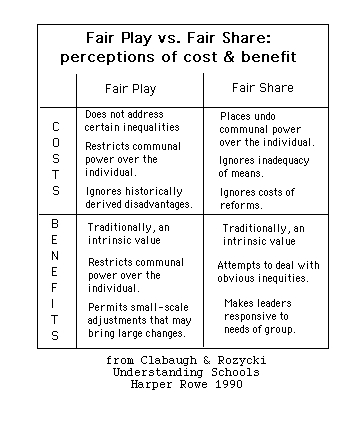

Given a fair play theory of justice, the principal was right, I should have given Harry an F. That's because under fair play no one is granted special consideration regardless of their circumstances. But my grade was based on the "fair share" theory of justice. Here, as in horse racing or amateur golf, the rules help even things up. The slowest horse is assigned the least weight. The worst golfer gets the biggest handicap. The point is to give those with less ability some reason to compete.

Adopting a fair share stance is fraught with problems. One difficulty is deciding what criteria to use to select people for compensatory breaks. There are many possibilities. Native intelligence, effort, impoverishment, dysfunctional family life, age, and race are obvious possibilities. Which ones should we choose and which ones should we ignore? And once we decide which handicaps count, there still is the problem of deciding how handicapped someone must be to qualify. If intellect is to be compensated for, for instance, we then have to decide how slow a youngster must be before we grant him or her special considerations?

Finally, we have to decide how much weight each criterion deserves. For instance, should being intellectually challenged count for more or less than being destitute? Or should being a minority matter more or less than being impoverished?

These are such difficult issues that educators often are tempted to bag the whole fair share thing and, adopting a fair play stance, make no special allowances for anyone. But when fair play is totally unmitigated by any fair share considerations, all special accommodations disappear. And that results in a Dickensian world. "You're deaf and need someone to sign for you, kid? Why don't you just forget about school altogether." "Can't get up the school stairs to your next class in that wheelchair, son? It sure sucks to be you!"

Deciding when to apply fair share or fair play principles of justice is one of the most important decisions an educator makes. It is one of the most difficult too because the choice is exquisitely sensitive to circumstances. When it comes to assigning grades, for instance, it probably should matter whether the student is a first grader or a senior. And it also is important if the grade counts for something like college admission or establishing eligibility for a scholarship. There is a lot more to think about too.

The fair share or fair play question isn't just about grades either. Educators choose between these competing principles of justice every time they decide how to apportion any limited resource. Consider a teacher's time. If he or she spends a lot of time on one troubled youngster, other kids probably end up without enough attention. Yet if the teacher chooses a strictly fair play assignment of time, kids who desperately need extra attention are left to take on water and sink. Similarly, if fair share concerns cause a school district to spend a great deal more per student on special education, kids in general education suffer. But a strictly fair play assignment of resources eliminates special education altogether.

Of course, the fair share or fair play dilemma is not limited to schooling either. Remember Casey Martin, who won a decision in February of 1998 allowing him the use of a cart on the Nike PGA Golf Tour? Martin, 26, was born with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome, a disease affecting the use of his right leg. In Martin's case, the fair share theory of justice won out -- probably because tournament officials did not think granting him the use of a cart severely compromised the fair play theory of justice that they ordinarily rely on. The fair share vs. fair play tension plays out on the national political scene as well. The affirmative action debate, for example, essentially involves choosing between fair share and fair play priorities.

It would be nice if educators didn't have to choose between fair play and fair share. But they do -- all the time. The best we can hope for, then, is that they make these choices wisely. Given that a lot of educators don't even recognize that these two competing conceptions of justice even exist, however, one wonders how often such wisdom prevails.