ON THE VIABILITY OF A CURRICULUM LEADERSHIP ROLE

Avoiding Confusion of Role and Function

©2003 Edward G. Rozycki, Ed. D.

RETURN

Links Checked 3/14/18

On Modeling the Curriculum

Imagine an automobile designer fixated on a single goal: reduced fuel consumption. Imagine further that he is not particularly well acquainted with normal conditions of driving, e.g. congested traffic, low speed limits, hilly and pothole‑filled roads. Imagine, finally, that he works for a company so bereft of automotive knowledge that his designs are put directly, uncritically, into production.

Ignorant of driver and passenger needs for comfort and safety, he designs web slings for seats. A light gauge plastic body covers an aluminum frame designed to hold a motor and drive train. He does not know that cars hit bumps or have accidents. The motor itself can propel the car a thousand miles on a gallon of gas if run no faster than ten miles an hour. There is no muffler -- it costs mileage. Acceleration is from zero to ten miles an hour in thirty seconds.

A curriculum "designer" aims for increased reading levels of prospective high school graduates. His design of sequenced criterion‑referenced mastery materials looks plausible; and it looks plausible for one reason only. Most educators are in the position of the automotive designer caricatured above: they either do not know, or misapprehend the classroom contexts in which these materials must viably interact if they are to have even a chance to affect reading ability. It is no little assumption that such outcomes as reading ability can be directly affected through curricular treatments. (Sarason, 1982)

Let us look at the complexity that can plausibly be argued to exist in a school environment. The happiest of universes for the curriculum interventionist is one in which there is a direct and fairly linear relationship between variables of curriculum change and student educational output, e.g.

So it is that if students do not achieve up to expectations on standardized tests, common practice nowadays removes "frills" from the curriculum, i.e. music, art, recess, and subjects students to "test-preparation" classes in more or less direct proportion to their "low-achievement."

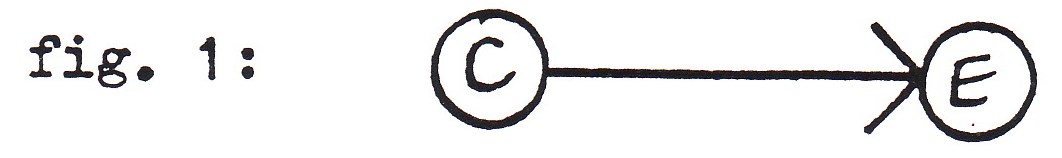

But clearly this simple model may offer difficulties which we can illustrate if we graph a hypothetical relationship between the variables thus:

We see that even with a simple model such as that given in figure one there may be optimal degrees of intervention before or beyond which unwanted results are effected. Perhaps, as many teachers report, there is a point at which boredom and rebellion against "test-preparation" sets in which influence test scores negatively.

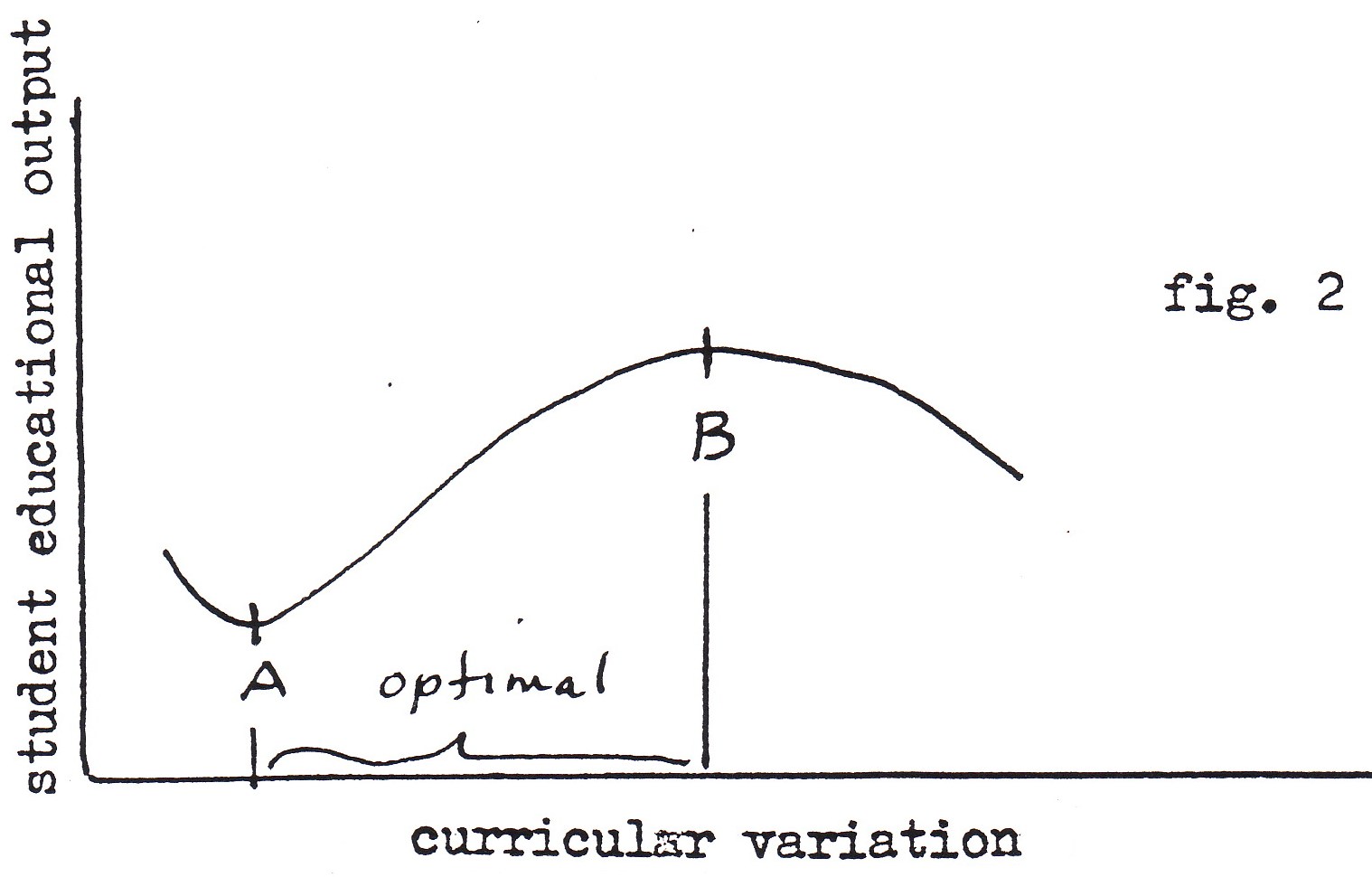

Benjamin Bloom's much more complicated model also presumes an unlikely simplicity. (Bloom, 1982)

This is another non-interactive model that begs a host of interesting questions:

a. Is instructional quality independently specifiable apart from the tasks and the populations in interaction with which it is embedded?

b. Are there not contextual influences, e.g. bells, programmatic considerations and the like that may be determinants?

c. Need the "learning relevant" cognitive and affective entry behaviors be determinable in advance of defining the task variables, in order to distinguish them from behaviors that are presumeably not relevant?

d. Is there no cultural variation here, i.e. is relevance of entry behavior‑types and "quality" of instruction absolute?

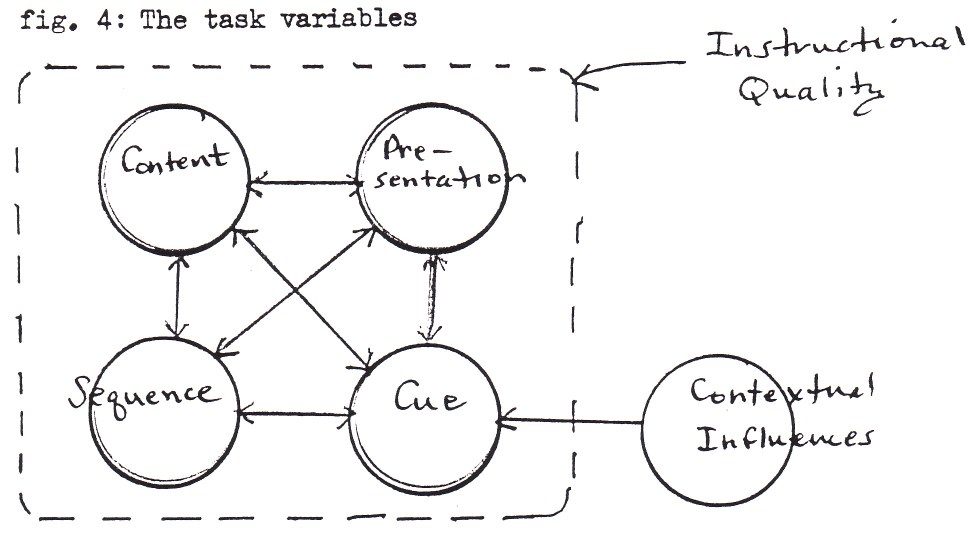

I would suggest, for example, that the task variable itself is complex and interactive consisting of at least the following sub-variables: content, presentation, sequence and cue.

That is, a teacher must have some idea of what to present (content), in what manner (presentation), in which of many possible orders (sequence) under what conditions (cue). Is the class restless; is the period short; has there just been a disturbance; are the children unusually attentive? It is apparent that instructional quality is, on this model, not another external variable, but rather is an assessment of how the variables of content, presentation, sequence and cue meet some standard of optimal interaction.

We can see that if we measure instructional quality as a composition of the four task variables, contextual influences may affect instructional quality independently of those variables the teacher has control over. It is painful common sense that a "good" teacher in one institution may be less than sterling in another.

But contextual influences affect student entry behavior as well as task variables. So the model we are looking for is considerable more complex than Bloom's. An interesting consequence of the model of figure 4 is that high quality instruction may require that the content variable be drastically reduced in value. For example, a classroom difficulty in presentation might require a quick review of old material, a slowing down of the pace or a resequencing of already presented material. (Bloom's mastery technique recognizes this although his model is too simple to illustrate it.) To the extent that a curricular change variable (see figure 1.) feeds into content and nothing else, to that extent must curricular variation have a tenuous -- if any -- effect on educational outcomes.

The upshot of the argument presented so far is that curriculum intervention cannot restrict itself to matters of content. But neither is concern with presentation and sequence sufficient in addition. Like the auto designer we imagined above we will build inoperable curricula unless we take into consideration the realities of the driving, i.e. the classroom, experience. Who can specify -- in advance and at a distance -- cue (not to mention the variations caused by contextual influences)? You don't teach driving by specifying arm and leg movements in response to visual and kinaesthetic cues: this is neither scientifically nor practically feasible. Without the feedback of relevant ethnographic data from the classroom, I suspect curricular intervention to any positive effect is unlikely.

Leadership Roles in Curriculum Intervention

Not every group of people, even if they are in close proximity, constitutes an organization. To postulate an organization is to hypothesize about interactional constancies. Organizations may be analyzed in a variety of ways which may not be congruent. For example, an organization analyzed in terms of some traditional conceptions of role may not exhibit the same structure, if any, when analyzed in terms of functioning units. This is important. The tasks it makes sense to assign to roles, e.g. program monitoring, it may not makes sense to assign in terms of functional efficiency.

We may distinguish among organizational tasks in the following helpful, if rough, manner: some tasks are durative, others are dispositional. Durative functions tend to be regular, routinizable and recurrent. Dispositional functions arise as other system "variables" show a specific configuration; they may be rarely performed, or irregularly performed, depending upon circumstances. Monitoring, adjusting and coordinating functions tend to be dispositional.

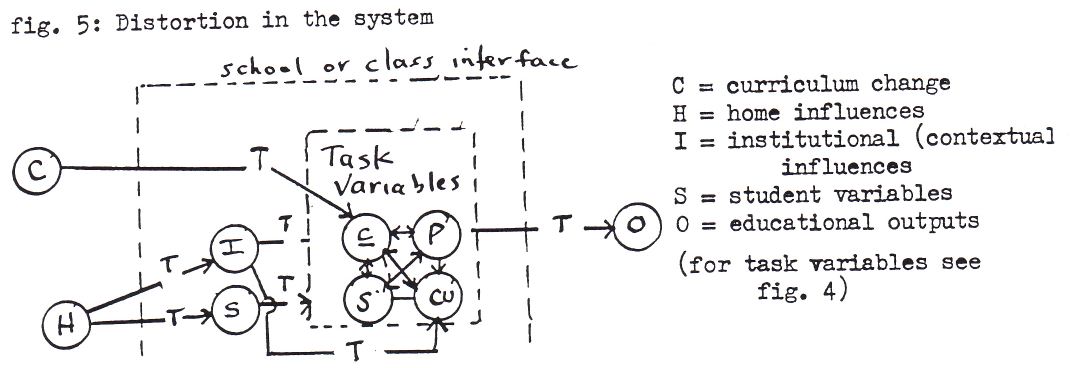

Roles are an entirely other matter. They may or not be related to activities which maintain the functioning of the organization -- this often depends upon the history and culture in which that organization is embedded. What is important for our purposes is this: it may be functionally destructive to assign to a leadership role dispositional functions, e.g. coordination, evaluation, etc. solely to maintain an organizational tradition. Isolation of dispositional functions gives rise to another problem: distance from the activity needing coordination introduces communication distortions. Another diagram might clarify this:

T represents a transmission variable that intervenes between any other two variables and increases in effect the greater the"distance" between them. T is not shown in the class or task interaction to simplify the diagram. It is reasonable to assume that distortions, e.g. delays, missequenees, miscues, and garbled information are more probable, the more dispositional functions are distanced from the site of their optimal effectiveness. Indeed, an important problem is exactly this: what is the site of their optimal effectiveness? It is probably mistaken to assume that traditional role distinctions in schools, e.g. teacher, aide, student, principal, supervisor, curriculum specialist, optimally locate dispositional functions.

Locating curriculum leadership functions

By leadership functions we will mean what we have heretofore called dispositional functions, e.g. coordination, content selection or adaptation, methodological choice, sequencing determinations. It is a truism that the psychological and social theories one espouses play a significant part in how one conceptualizes the relationship between curriculum development and classroom practice. A behavioristic, black-box approach reinforces the traditional notions of role found in our educational bureaucracies and locates -- quite conveniently -- curriculum leadership at some remove from the classroom milieu. This approach has failed. (Sarason; Hurn, 1979) In this paper we will adapt an interactive, systemics approach. Clearly, from the concept of leadership function as dispositional, it follows that to reduce transmissional distortions, much curricular leadership will have to be located within the classroom milieu. This has, however, potential for political disturbance since it violates traditional role assumptions presently operative in schools.

For our purposes, curricular leadership will be found at various levels in the school hierarchy. Furthemore, we will make no assumptions that necessarily locate it at some given remove from the classroom milieu.

Certain curricular leadership functions will be located in the role of teacher, or classroom aide or student monitor. Cueing responses, content expansion or revision, and mode of presentation will be some of these. These functions take time to be exercised and location is restricted for maximal effect. Additional leadership functions such as coordinating among classes, selecting students with appropriate skill levels might be located elsewhere, depending upon the institutional resources available.

We must have a baseline in terms of which we can tell whether our organizational variations are being optimized. Let us say that a treatment is pedagogically efficient to the extent that it enhances an educational outcome. (Rozycki, 1982) How can we tell whether a change in the location of leadership functions is an improvement? By determining its effect on pedagogical efficiency.

Let us assume that certain manipulations of the task variables will optimize pedagogical efficiency under certain conditions -- there may occur certain conditions that completely preclude pedagogical effectiveness, i.e. pedagogical efficiency = 0, and these conditions may be beyond the control of the curricular leader in the particular context.

For example, a new teacher is given a class where none of the kids speaks English and more than half are suffering toothaches, depression or fever. Or, classroom interruption by visitors, wandering students, loudspeaker announcements and candy sales persistently interrupt activities. Or there is a very attractive, new student in class that raises the distraction level of marginal students to the interference point.

Leadership functions at further remove must consist in providing resourees and information and removing impediments to optimal functioning at the local level. Part of the leadership function must be to inform all those who participate in it of the outcomes in terms of which pedagogical efficiency is judged.

Any outcome which cannot be pursued by adjustment in local task variables in the conditions in which they are manipulated must be rejected as unfeasible. Or, which is probably politically wiser, such outcomes must be given an "in‑house" interpretation which permits their realization.

On Tight Coupling and the Possibility of Curricular Leadership Functions

Public schools are often criticized as not tightly coupled enough to enable effective curricular leadership. (Pajak) The press of our arguments here is to the contrary conclusion: because traditional role definitions of leadership distance their actors from the scene of action, and because the probability of transmission distortions increases with such distance,tight coupling, given the standard, pupil, aide, teacher, principal, specialist hierarchy, must be counterproductive. To the extent that loose coupling allows for practical relocations of leadership function at different levels, it must enhance pedagogical efficiency.

In some aspects, the most loosely coupled of schools is tightly coupled. To wit: court mandated programs for special education and racial integration. Irrespective of the positive moral justifications for such programs, it is questionable whether they have enhanced the pedagogical efficiency of the average school. Certainly, these programs have worked to ossify even more the role distinctions of the traditional schooling hierarchy.

One might argue that given sufficient uniformity of goals by staff, parents and administration, and within narrow confines of traditional conceptions of proper school activity, curricular leadership is likely to be pedagogically efficient even in a tightly coupled organization, for example, a "strictly run" parochial school. That is likely true. But then there is no problem of curricular leadership and the considerations of this paper are otiose.

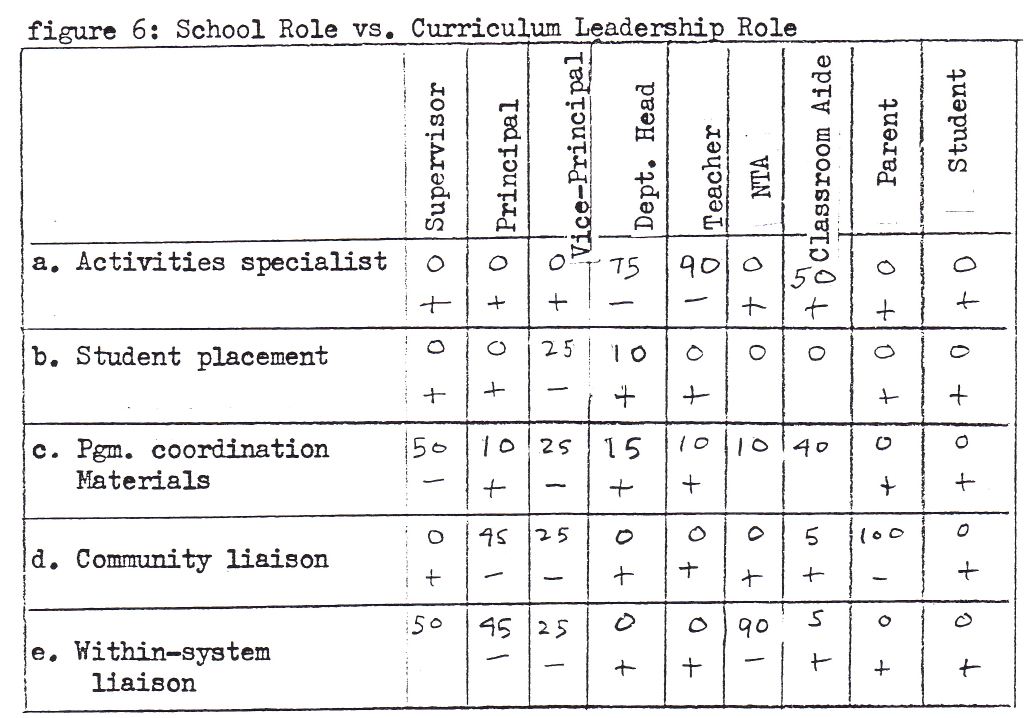

We might imagine that a viable program with adequate curricular leadership would share many skills among its participants. We will attempt to define new role types congruent with the interactive model we have adopted. These are:

a. activities specialist and leader (facilitator)

b. student placement and skills assessor

c. materials acquisitions and program coordinator

d. community liaison, troubleshooter

e. within‑system liaison, troubleshooter.

Ideally, these jobs ought to be shared or rotated and everybody should work -- if only minimally -- in a"teacher"- facilitator (activities leader) role. Let us examine the staffing of a contemporary junior high school and observe the discrepancy between actual and ideal functioning on our model. In figure 6 below we find various organizational roles with a rough percentage "guesstimate" of how each relates to the curriculum leadership functions given immediately above.

Lacking a specific context it is unwise to speculate about what would be an optimal level of participation in each curriculum leadership role. + indicates a probable increase, ‑ a probable decrease in the present percentage "guesstimate" of functioning.

I doubt that the constituencies exist or could be speedily built to support the somewhat radical reorganization of the school suggested in figure six. It might be best, perhaps, to view the problem of change in curriculum leadership as a long term problem and work in the manner of Goodlad or Sarason to support change-oriented groups in the classroom context on a small scale. I am not sanguine about this possibility given the patience it requires.

|

See, also, Revisiting

Mastery Curriculum

|

References

Bloom, Benjamin S. Human characteristics and school learning. New York. McGraw. 1982

Goodlad, John What Schools Are For. Phi Delta Kappa 1979

Hurn, Christopher J. The limits and possibilities of schooling. Boston. Allyn. 1978

Pajak, Edward. Schools as loosely coupled organizations. Educational Forum, 44, 83-95.(Nov. 1979)

Rozycki, Edward G. "Increasing teaching efficiency: the evaluation of method." (1998 -- originally 1982) Available at http://www.newfoundations.com/EGR/Increasing.html

Sarason, Seymour B. The Culture of the school and the problem of change. Boston. Allyn. 198